Link to NTBS Preliminary report:

Contact of Mexican Navy ARM Cuauhtémoc BE 01 with the Brooklyn Bridge

1.2 Accident Events

On the planned departure day, May 17, a sea pilot boarded the vessel about 1902, and a local docking (harbor) pilot arrived about 1945. Both pilots conducted a master/pilot exchange with the ship’s captain. The pilots stated that the ship’s captain reported the propulsion and steering systems were in good order, and there were no deficiencies. The docking pilot stated that the time of the vessel’s departure was scheduled to coincide with slack tide (the time between ebb and flood currents at which the current was the weakest), which was to occur about 2011 that evening. Weather conditions were reported as westerly winds 10-15 knots, water temperature about 60°F, and air temperature about 77°F. Visibility was clear.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Brooklyn Bridge (site NYH1920) station predicted slack water, with a depth of 8 feet, at 2012, and 0.13 knots of flood current at 2018.

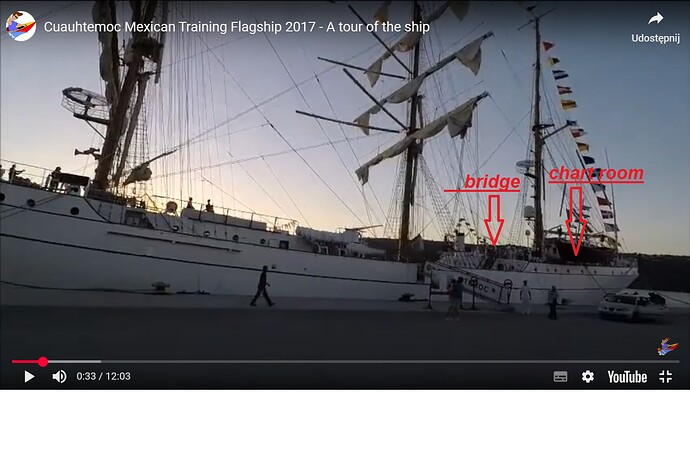

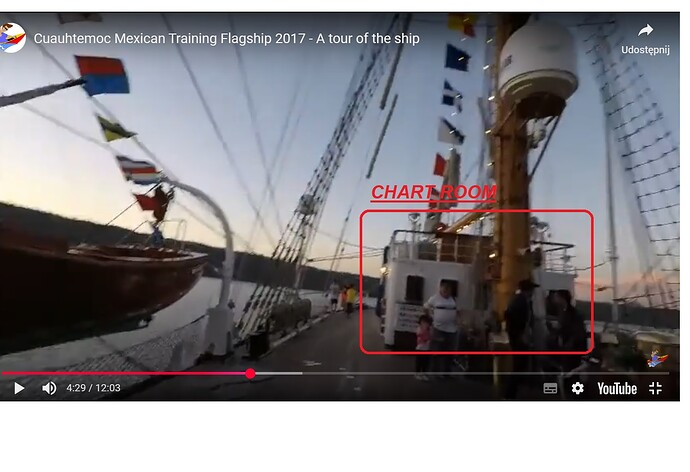

At departure, the ship’s captain and both pilots were on the open conning deck directly above the vessel’s enclosed navigation bridge. The docking pilot used the sea pilot’s portable pilot unit (a portable navigation support system containing real-time navigation data and other features for guiding vessels) throughout the transit. For the East River transit, several Cuauhtémoc personnel were positioned in formation on each of the horizontal yards (spars crossing the masts from which the sails are set) on the foremast and main mast, as well as the horizontal boom below the mizzen (aft) mast, and the bowsprit. All the sails were furled in their stowed position.

The vessel’s six mooring lines were let go about 2016. About 2019, the 2,800-hp twin screw tugboat Charles D. McAllister assisted the Cuauhtémoc off the pier. The docking pilot gave astern commands to the captain on the conning deck, which were acknowledged by the captain, translated to Spanish, and relayed to another crewmember on the deck below, outside of the navigation bridge. This crewmember then relayed the orders to crewmembers within the navigation bridge, where commands were inputted.

Between 2020 and 2022, the Cuauhtémoc moved astern and away from Pier 17 at 2.5 knots. Once clear of the slip, the docking pilot gave a stop command, gave a dead-slow-ahead order, and directed the Charles D. McAllister tug to reposition on the starboard bow of the Cuauhtémoc.[1] As the crew of the tug took their line in, the docking pilot ordered additional commands in the ahead direction.

The Charles D. McAllister began pushing on the starboard bow of the Cuauhtémoc. The stern of the Cuauhtémoc began to swing toward the Brooklyn Bridge. At the order of the docking pilot, the Charles D. McAllister stopped pushing against the ship, backed away, and maneuvered toward the stern of the Cuauhtémoc along its starboard side. Between 2023 and 2024, the vessel’s astern speed increased from 3.3 knots to 5.1 knots, and the harbor pilot called for nearby tugboat assistance.

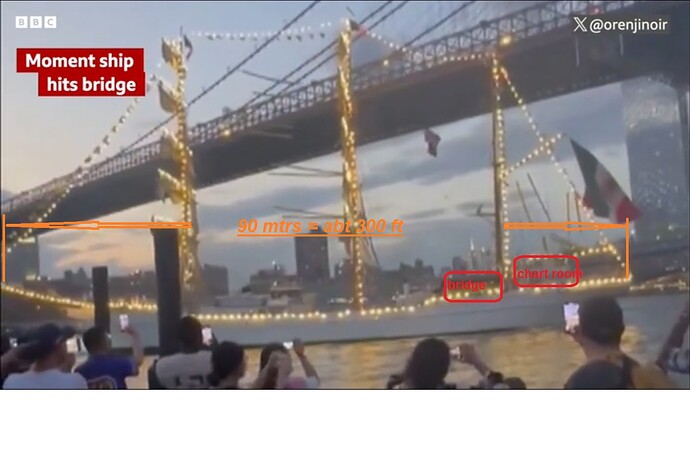

Starting at 2024:42, the upper sections of all three masts of the Cuauhtémoc contacted the underside of the Brooklyn Bridge, one by one. The mizzen mast contacted the bridge first, followed by the main mast, and then the foremast. The mizzen mast and main mast also struck the bridge’s no. 3 traveler (a moveable maintenance platform hung from traveler rails beneath the bridge deck that was used for workers to access areas of the bridge), which was positioned at its docking location near the Brooklyn Tower. The vessel was traveling about 5.9 knots astern when it contacted the bridge.

The Cuauhtémoc continued in the astern direction under the Brooklyn Bridge, and its stern contacted a seawall on the Brooklyn side of the East River. The Cuauhtémoc continued along, with its port side against the sea wall, and the vessel’s speed decreased. About 2027, the Cuauhtémoc came to rest against the seawall on the east side of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Automatic identification system data shows that, about 2028, the vessel moved away from the seawall into the river between the Brooklyn Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge. The crew then deployed both anchors.

The Charles D. McAllister remained on scene. About 2030, New York City Police Department and New York City Fire Department boats arrived and transported injured crewmembers to local hospitals. Later that evening, the vessel was towed across the East River to Pier 36 in Manhattan.